It’s been a rare high-calorie week for me on the culture front. I’ll be honest, the creative side of me has been teetotaling hard the last few months. The billboards and storefronts of my mind are filled with all the books I haven’t read and all the movies I haven’t seen, and not a drop to drink. And so, with the necessary degree of shame, I confess that in between staring at my screen for ten hours a day and swinging kettlebells and date night, there has not been a lot of longform consumption. Podcasts do not count. The rivers have run dry.

This week, though. This week I did the Lord’s work. I finally got around to watching Louis Malle’s My Dinner with Andre. I went to a Bolaño memorial in South Street Seaport hosted by his translator Natasha Wimmer, Álvaro Enrigue, and Francine Prose, and the next day I came across a Tweet sharing a full 2,154-page copy of Proust’s In Search of Lost Time, but with a ‘lol’ inserted at the end of every sentence. I had a Topo Chico with dinner every night. Lime.

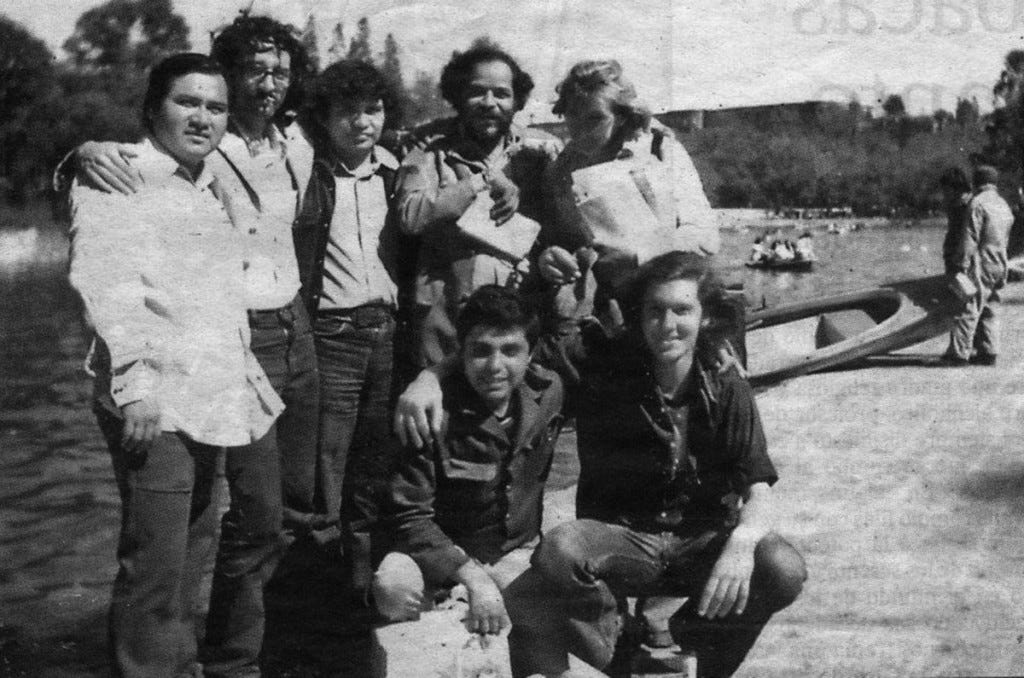

A silver lining from the throes of Abstemious August: I had the joy of catching up with several long lost friends. Some I haven’t seen in months, some of them years. Early-twenties friends, what can I say. The ones you turned the corner with. Back when your hair was long and your body could handle anything and everyone you knew was a yip hurled skyward from the crest of a fast-moving wave. You could feel it even then: that sense of adjacency so totalizing and precious it will rage against the storms of adult life simply to endure. Maybe you can feel it now: what remains of the wave.

Then comes the Parting of the Ways. The Parting of the Ways arrives just after the Turn and just before the dance of a thousand other things, all of which feel like swaying. We sway for so long, right down the line.

What are we swaying to? What’s on the other side of a seashell held up to your ear? It could only be the Song of Unstoppable Change. The whispering of sycophants, and the great migration of souls. We sway right up until the day the music cuts out, and you and I and so many others are released back into the city’s summer throng. The ceremony of already fallen rain, gathering itself back into the air. Eternity’s hazy glow.

Set in the Café des Artistes on Central Park West, My Dinner with Andre makes this dreamlike milieu its home. The plot, to the extent there is one, exists within the confines of two friends’ conversation over dinner one night in 1980s New York. The characters, played by Wallace Shawn and André Gregory, are satirical distortions of the actors themselves. Wally is an embattled playwright always hustling to make ends meet; Andre is a celebrated theater director who several years ago disappeared from city life altogether, in pursuit of artistic freedom and a haphazard personal truth. At the film’s outset, Wally informs us by voiceover that they have grown estranged. In fact, he’s been dodging Andre’s invitations for some time.

My girlfriend fell asleep after thirty minutes. The first half is dominated by a very one-sided recapitulation of Andre’s time as vagabond—heady brushes with experimental communities in Europe, hallucinations at a Christmas mass on Long Island, a trip to the Sahara with a Buddhist priest who can balance his entire body on two fingers. At best, Andre appears as a kind of eccentric uncle, mysteriously wealthy and ready to blow this thing wide open after a few Manhattans. At worst, a haughty Brahmin who wields privilege and spiritualism as a bludgeon.

Still, for all it prevails upon our attention span, the film lacks artifice. Something about the casual but captive atmosphere is irresistible, trance-like. Every now and then, Wally interrupts with some filler follow-up, but for nearly an hour, the characters hold fast to the comfort of their trials and tribulations—the half-formed thoughts that get us through the day, the menu of commiserations we provide to fill the silence. Over the course of their dinner, however, the scripts reach the end of their half-life. The two men are no longer content merely to break bread—to talk, and be talked at. Some old unspoken rupture hovers in the air between them. They start to have things out.

One of the great and unexpected privileges of my last few years has been witnessing the leaps my friends have made in their lives. To catch a glimpse of it, the step that marks the leap, is a jolt and a half. A shock, since in that instant your connection to them is severed. A shock, because somewhere down the line, that connection will boomerang back to you in the form of an inimitable human being, someone capable of proficiency and commitment and love and conviction and freedom.

All of this is no doubt a protracted and heavy emotion to process. We can easily mistake the marks and impressions it leaves upon us for transgressions, even wounds. Ultimately, the final state—un-possessive joy—demands a new frame of reference in order to be perceived. The right kind of light, that sort of thing.

Maybe it’s just me, but from childhood all the way up to college and through most of my twenties, the feeling of friendship often appeared limitless. I woke up to my contained little life free of dread and full of direction. I had a strong sense of promise and a weak sense of time.

Beyond the edges of my twenty-something vision, however, the doors out on the periphery were quietly beginning to close. We develop a sense of loss before we develop a sense of time. A rather banal acknowledgement announces the middlegame: We are the inhabitants of an ever so slightly receding shore.

The Parting of the Ways arrives. This is it, we say, this is what it’s all about. The boundless capacity young people have for connection is one thing; the fragile bonds we must sustain across time and space and more immediate dependencies, another. Friendship ceases to be simply the sensation of comfort or closeness. The music has changed. We are now taking part in a ritual of call and response, and no one is ready. Oh, we’re going to be in each other’s lives forever? Where are we going? What will we talk about? In the end, or at least where I am now, the measure of friendship is taken by the degree to which it is affirmed. By what remains of the wave.

“Well, have a real relationship with a person that goes on for years, that’s completely unpredictable. Then you’ve cut off all your ties to the land and you’re sailing into the unknown, into uncharted seas. I mean, you know, people hold on to these images: father, mother, husband, wife, again for the same reason: because they seem to provide some firm ground. But there’s no wife there. What does that mean, a wife? A husband? A son? A baby holds your hands and then suddenly there’s this huge man lifting you off the ground, and then he’s gone. Where’s that son?” (André Gregory, My Dinner with Andre)

Here’s the other thing: When we live without time, we can afford to be unspecific and hand-wavy with our fears. We might have a vague vibes-based sense of what they look like, but for the most part we don’t give them form. Why should we? We’re all going to live forever, and nobody looks at the underside of their shoes for long. For as long as we can, we neglect our fears. There they are, locked in some basement of the brain and languishing in impressionistic obscurity, and here we are, with the wind at our back and basically zero motivation to march them out into the light of day.

Then we turn the corner. Suddenly the Song of Unstoppable Change is all around and crescendoing all the while. Things are happening to you. What are they? Who are you? You read the occasional book. You grab drinks with friends. Maybe you think about going to therapy. These techniques supply the notation necessary to join the fabric of change into an intelligible bar of music. It is easy to forget—fear only wants to be seen.

The same is true of dreams. Keep them ambiguous and undescribed, and you have nothing to lose for a long time. The universe will not resist. A conspiratorial thought, really: most of civilization is engineered to curtail uncertainty of outcome and will support you in your dereliction of duty. It will even provide you with the script, a language of acceptability with which you can justify the choices you have made in a social setting. Another way of not looking. And so we abstract ourselves away from the gut truths of our identity and existence.

Look at your dreams head-on, however... To do that is to bring fear into the encounter. The dream is not a safe place: it is the perfect composite of everything you have taken and put back into the world. It is your capacity to imagine a future, and also to fail in the present moment. In culture the dream has become little more than a trope, something intangible and juvenile, but in practice it is a step against civilization. It emanates from every conceivable shade of experience you have to offer: trauma, hope, despair, determination, derangement, transcendence. Enter the dream, and now you are risking something, something as little as a passing whim and as vast as the final statement of your life on earth.

Let’s take the counterfactual: Imagine a world where fear and dream have not been alienated. Imagine a society which does not embalm our fear, so that we may bury it. Imagine standing next to your aspirational twin—the half of you who is consumed by still failing endeavors, but who lives in service of a contrary vision.

If within our ranks there is a messenger from this Other World, it is Bolaño. The one and only, and there can only be one. A contemporary Dante, if hell were the inauthentic life and purgatory were a noisy bar.

What’s this Other World like? You might call it fantastical, but only in the sense it is clearly not our own. It is also a decidedly anti-bourgeois landscape, stripped of convention and creature comforts and four-hour lives. A world of weak knees and strong brew, populated by an immutable cast of characters, all of whom hail far from the reaches of power. More 1980s Times Square than Central Park West. More Cortazár’s Other Heaven than Louvre Paris. It is a community of souls who live in the dream, or on its edges, and the border between the reality of the dream and the dream that is reality is clarified in the starkest of imagery. Subterfuge and corruption, popular upheaval and genocide, creation and destruction. The art dealers of the Americas are spies, and the poets carry guns in their notebooks.

“[A]n environment whose language they refused to recognize, an environment that existed on some parallel plane where they couldn’t make their presence felt, imprint themselves, unless they raised their voices, unless they argued…” (2666, p. 112)

“At some point your shadow has quietly slipped away. You pretend you don’t notice, but you have, you’re missing your f*cking shadow, though there are plenty of ways to explain it, the angle of the sun, the degree of oblivion induced by the sun beating down on hatless heads, the quantity of alcohol ingested, the movement of something like subterranean tanks of pain, the fear of more contingent things, a disease that begins to become apparent, wounded vanity, the desire just for once in your life to be on time. But the point is, your shadow is lost and you, momentarily, forget it. And so you arrive on a kind of stage, without your shadow, and you start to translate reality or reinterpret it or sing it.” (2666, p. 122)

In Part One of Bolaño’s 2666, which I previously wrote about here, a team of three literary critics set off on a boys’ trip to a Swiss lunatic asylum. They’re on the hunt for the mysterious German writer Archimboldi, but today they seek the counsel of a once-acclaimed English painter who cleaved off his right hand and attached it to his own self-portrait. It’s a bit of inside baseball, in the sense that this painter’s name is Edwin Johns, and we have ourselves a real-life 20th-century Welsh portrait painter by the name of Augustus Edwin John. That, and the fact the apple of their eye Archimboldi is an apparent knock on the 16th-century Italian portrait painter Giuseppe Arcimboldo. Writer, painter, painter, writer. Johns’s Ahab to Archimboldi’s Ishmael. Echoes, reverberations, buzzed whispers… It’s a quest!

“‘And as far as coincidence is concerned, it’s never a question of believing in it or not. The whole world is a coincidence. I had a friend who told me I was wrong to think that way. My friend said the world isn’t a coincidence for someone traveling by rail, even if the train should cross foreign lands, places the traveler will never see again in his life. And it isn’t a coincidence for the person who gets up at six in the morning, exhausted, to go to work; for the person who has no choice but to get up and pile more suffering on the suffering he’s already accumulated. Suffering is accumulated, said my friend, that’s a fact, and the greater the suffering, the smaller the coincidence.’

‘As if coincidence were a luxury?’ asked Morini.

At that moment, Espinoza, who had been following Johns’s monologue, noticed Pelletier next to the nurse, one elbow propped up on the window ledge as with the other hand, in a polite gesture, he helped her find the page where the story by Archimboldi began. The blond nurse, sitting in the chair with the book on her lap, and Pelletier, standing by her side, in a pose not lacking in gallantry. And the window ledge and the roses outside and beyond them the grass and the trees and the evening advancing across ridges and ravines and lonely crags. The shadows that crept imperceptibly across the inside of the cottage, creating angles where none had existed before, vague sketches that suddenly appeared on the walls, circles that faded like mute explosions.

‘Coincidence isn’t a luxury, it’s the flip side of fate, and something else besides,’ said Johns.

‘What else?’ asked Morini.

‘Something my friend couldn’t grasp, for a reason that’s simple and easy to understand. My friend (if I may still call him that) believed in humanity, and so he also believed in order, in the order of painting and the order of words, since words are what we paint with. He believed in redemption. Deep down he may even have believed in progress. Coincidence, on the other hand, is total freedom, our natural destiny. Coincidence obeys no laws and if it does we don’t know what they are. Coincidence, if you’ll permit me the simile, is like the manifestation of God at every moment on our planet. A senseless God making senseless gestures at his senseless creatures. In that hurricane, in that osseous implosion, we find communion. The communion of coincidence and effect and the communion of effect with us.’” (p. 90-91)

There are two sides of a dialectic here that I keep turning over. Suffering is accumulated… and the greater the suffering, the smaller the coincidence. Then, the rebuttal: Coincidence isn’t a luxury, it’s the flip side of fate, and something else besides… Coincidence, on the other hand, is total freedom, our natural destiny.

Two coexistent worlds, each on the opposing sides of a veil. Replace the word suffering with fear, and the word coincidence with dream, and you know what I’m talking about. In a way, we’re back at the table with Wally and Andre—two men in the same city eating the same dinner, excruciatingly unable to understand the other’s point of view.

Interestingly, Wally’s line of retort seems to mirror that of Morini. They both suggest that the absolute freedom into which Johns and Andre retreat is inaccessible to those outside the realm of privilege. To them in that moment, the dream is little more than the refuge of the bourgeois mind. Their fear is doing the talking.

I’m reminded of a passage from The Savage Detectives in which the poet and vagabond Ulises Lima describes his wayfaring along the continent:

“Of all the islands he’d visited, two stood out lol. The island of the past, he said, where the only time was past time and the inhabitants were bored and more or less happy, but where the weight of illusion was so great that the island sank a little deeper into the river every day lol. And the island of the future, where the only time was the future, and the inhabitants were planners and strivers, such strivers that they were likely to end up devouring one another lol.”