“We do not see the world, we see the light it throws back at us… That these impressions should have an objective existence, discernible not only by the inner ‘I’ but by other people too, for instance during a dissection of the eye, is no odder an idea than that the soul should exist independently of the body through which it expresses itself.”

Karl Ove Knausgård, “All That Is In Heaven”

As I write this, I’m standing at my desk in my bedroom because two days ago I threw out my back deadlifting a tiny amount of weight and it actually hurts to sit down for long. Whenever my health takes a hit like this, I find myself unconsciously accepting my new reality as mysteriously permanent. For someone who reads and writes a decent amount, usually out of guilt, it might surprise you that I have a very hard time imagining something other than the primary experience of my body in the world in that instant. Right now, I am an invalid, and I will never leave my house again. I have to remind myself, over and over, that the world as I am experiencing it is one of thousands of available perspectives, and that my default response—usually, grumpiness—is little more than a porthole window into the plenum. How to break the spell?

A few weeks ago, I came across perhaps the most serene piece of music I’ve ever heard in my life: “Stone in Focus,” by the ambient icon Aphex Twin. I’d had a perfectly meh day and was walking aimlessly around the neighborhood, bundled up in a baggy sweater and sweatpants and using my headphones as earmuffs. After the hottest summer in history, it was one of the first truly cold evenings of fall.

The track, also known as #19 on Selected Ambient Works Volume II (1994), is impossible to find except on the original vinyl and, of course, YouTube, where it has apparently won the hearts of the white noise community. As a composition, the song could not be more uncomplicated, consisting of three interwoven tracks on loop—a palpitating metronome, a three-chord progression on pipe organ, and what sounds to me like raindrops (a harp??) striking the surface of an ocean at night. I don’t know exactly what’s going on here, all of what I just said about the song could be spectacularly wrong, and that’s okay. I don’t particularly care to interpret the sacred mysteries.

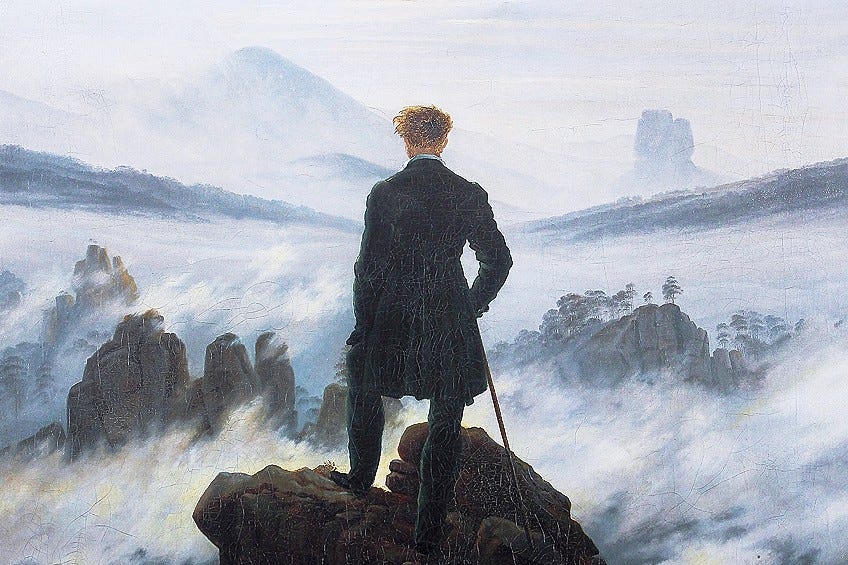

What I do know is, when lucky #19 rose up from my queue that listless, good-for-nothing Monday, something within me gave way. My present-day life slowed, receding until it became a kind of tableau vivant, one of those staged photographs which reimagines a classic piece of art. Where had I gone? By some minor miracle, I was back in college, ambling along in the first snow of winter. Nothing to do, not an ounce of dread in my body, thinking about life and who I wanted to be and how it’d all shake out. The streetlamps in the darkness, the empty buildings, the crunch of salt under my feet… I did not know why, some ten years later, this moment had spontaneously returned to me. I also couldn’t seem to isolate the emotions welling up inside of me—whether I was in fact fearless, then, or simply hadn’t learned what fear was, whether I was full of love for my friends when we were there, together, or now, with remove. Maybe the object of memory was simply this tense ambivalence, anticipation and apprehension at once, as if I were licking the last drops of honey from a razor’s edge. For ten minutes, time curled back, transposed. I might as well have been waltzing through an ancient ruin in the year 5,000, floating like a wraith through the halls of a life which I had lived, but was no longer mine.

Of course, sensations like this are hardly unique to me; the transportative powers of music are well-established, to the point of cliché. Recent studies have shown that music encodes itself so deeply in the brain’s memory centers that there exist, for each of us, songs which are in a sense inextinguishable—accessible even to those with chronic cognitive injuries, such as dementia and Alzheimer’s.

Hold up, though: this song wasn’t a memory at all. I was hearing “Stone in Focus” for the first time, and yet my brain still performed the sensation of nostalgia anyway. It was as if the music were a kind of dusty mirror, summoning images unique and familiar to every onlooker. In other words, the song could theoretically evoke a specific moment in the lives of an infinite number of people. If that were true, what is it we’re all seeing? Are we all visiting the same room in our imagination?

In his novel The Unbearable Lightness of Being, Milan Kundera describes Nietzsche’s concept of eternal return: the idea that things can “appear without the mitigating circumstance of their transitory nature.” For Kundera, eternal return is a kind of existential gravity, a sum of the covenants we have made with the people and places of our lives, and we can contrast it with weightlessness:

“If every second of our lives recurs an infinite number of times, we are nailed to eternity as Jesus Christ was nailed to the cross. It is a terrifying prospect. In the world of eternal return the weight of unbearable responsibility lies heavy on every move we make… The heavier the burden, the closer our lives comes to the earth, the more real and truthful they become.

Conversely, the absolute absence of a burden causes man to be lighter than air, to soar into the heights, take leave of the earth and his earthly being, and become only half real, his movements as free as they are insignificant.

What then shall we choose? Weight or lightness?”

For Kundera, this is the humdinger of a lifetime, the final boss, and so he forces it upon his characters: the casanova Tomas, his merciful wife Tereza, the rebel Sabina, the dreamer Franz. He draws a parallel to music—specifically, Beethoven’s last string quartet—in which counterpoint is established through two conflicting motifs: “Es muss sein!” (It must be so!) and “Es könnte auch anders sein” (It could just as well be otherwise). Weight: the voice of fidelity, devotion, and conviction. Lightness: the voice of liberation, migration, and abandon. It’s a question of fate, really, and the degree to which its resolutions can be resisted.

In a scene with Franz, Sabina remembers standing with Tomas in front of her mirror as they each try on her grandfather’s bowler hat. For her, the hat’s meaning is multiplied: a reminder of her Bohemian grandfather, an inheritance from her dead father, a sex prop, a sentimental object from her time with Tomas. When she passes it to Franz, he cannot comprehend the gesture; its meaning is lost on him.

“The bowler hat was a motif in the musical composition that was Sabina’s life. It returned again and again, each time with a different meaning, and all the meanings flowed through the bowler hat like water through a riverbed…

While people are fairly young and the musical composition of their lives is still in its opening bars, they can go about writing it together and exchange motifs… but if they meet when they are older, like Franz and Sabina, their musical compositions are more or less complete, and every motif, every object, every word means something different to each of them.”

It is my entirely unsupported belief that, when music transports us, we are crossing an internal boundary (or maybe that is simply when we are most susceptible). Music attaches itself to us at the instant of a change of heart, or of self-conception, precisely when we push through the fence from lightness into weight, or vice versa. We hear it strongest in the final moments, right before the decision to leave—a break-up or farewell, a resignation, a big move. But we also hear it in the rush of arrival: “Yes.” “I’m here.” “I’ll stay.”

On our way to the border, we often experience what Sartre called nausea—an existential motion sickness, and a side-effect of the body’s adaptation to chaotic new surroundings. Nausea is the opposite of the porthole view; you are suddenly looking into the plenum full-on, having beautiful and terrible visions and overdosing on the anomaly of your existence, the parade of dying stars and astronomical unlikelihoods that led to you being here, now, making that infinitesimal left turn in the face of eternity.

What happens next? People begin to lose their distinguishing features. Even the ones we know and love come to hover on the edge of anonymity. Zoom out far enough, and the concept of the individual does not exist. We detach, dissociate, “lighter than air.” And then, suddenly, we perceive an equal and opposite force. Just as we leave the ground, we are confronted with the true weight of our own identity, our connections to others, an invisible but innate sense of duty and debts to be repaid. Zoom out far enough, and the distinction of the individual becomes vital as it never was before. Protect this man at all costs!

It is under the influence of nausea that the music imprints itself upon us, a motif, the meaning of which will constantly evolve as our own lives weather on and interweave with the lives of other migrants along the way. Maybe, in replaying my college transience, my brain was actually prompting me to remember that I had made a similar journey before. In this act of involuntary memory, I was supplying myself with a mental photograph to match the soundtrack accompanying my life. My mind was bringing me back to itself.

A curious sleight of hand, now that I think about it… Because in the process of being applied, that original memory has now to some degree been obscured, painted over. It is no longer ground zero; I cannot come back to it pure. Its meaning has been altered, and will be altered again each time it is retrieved.

This is kind of a big deal only because identity itself is nothing if not selective memory. Who I am, at a very fundamental level, is a direct function of who I remember myself to be. Shorn of that, I could be anything, anyone, anywhere, anywhen. Reality, in Sartre’s view, is the edge case. Under normal conditions, the world could “just as well be otherwise.”

It is a delicate thing: If I were to modify that subset of core memories, I could destroy myself. And yet, in the long arc of our lifetimes, we are choosing and changing them all the while. The border is also the precipice. Nausea, again.

Mercifully, music and memory step in to defrost the mirrors, illuminating a path forward. To think that nearly ten million people have tuned in to “Stone in Focus” and watched a snow monkey chill in a Japanese hot spring for ten minutes is undoubtedly cool. Ten million people crossing that border, dangling their feet off the precipice, the great transmigration of souls... They say the oldest musical instruments—flutes carved from bone and mammoth ivory—are more than 40 thousand years old.

In the end, the choice of melody—lightness, or weight—is what we will return to. Again and again, we are asked to affirm our path. And, personally, I wouldn’t have it any other way. Can a person truly be considered good if at some point they didn’t have the option to be evil? Can you really accept something to be true without going through the process of doubt? Can you remember anything if you have not first learned how to forget? The purpose of memory is not merely to recall; it is to provide your future self with the potential for change.

And so yes, each time a motif returns to us, it will depart in a new form, like a photograph of a dancer in which every after-image has been coded into the original. Like the tableau vivant, like the bowler hat, the classic comes to stand outside of its time. We are meant to hold onto it only briefly, hoping against hope that, in discovering some tangent part of our past, we might glimpse our own future.

“Everything that happened after I took the picture was also inside it, even though no one could see it, except me when I looked at it, and maybe also you, in the future, when you look at it, even if you didn’t even see the original moment with your own eyes.”

Valeria Luiselli, Lost Children Archive